協働の輪郭 | Group Form 第1回 「スケールの所在、匿名性のかたち」(インタビューイー/玉山拓郎 /現代美術家)

「協働」という言葉が意味するものは、単なる共同作業や役割分担ではない。現場で交わされる無数の判断や、形やスケールをめぐる曖昧な駆け引き、関係性の中で生まれる基準——その総体である。本連載「協働の輪郭」では、建築と美術の現場を行き来しながら、協働というプロセスが作品やプロジェクトに与える影響を探る。第1回は、現代美術家・玉山拓郎を迎え、名古屋城アートサイト2023と2025年の豊田市美術館でのGROUPとの協働経験を起点に、作品の匿名性やディテール、自律性、そしてスケールについて話をした。

玉山拓郎

現代美術家。1990年、岐阜県生まれ。

愛知県立芸術大学を経て、2015年に東京藝術大学大学院修了。

身近にあるイメージを参照し生み出された家具や日用品のようなオブジェクト、室内空間をモチーフに、鮮やかな照明や音響を組み合わせたインスタレーションを制作。最小限の方法で空間を異化、あるいは自然の理を強調することで、鑑賞者の身体感覚や知覚へと揺さぶりをかける

HP:https://anomalytokyo.com/artist/takuro_tamayama/

Instagram:https://www.instagram.com/takurotamayama

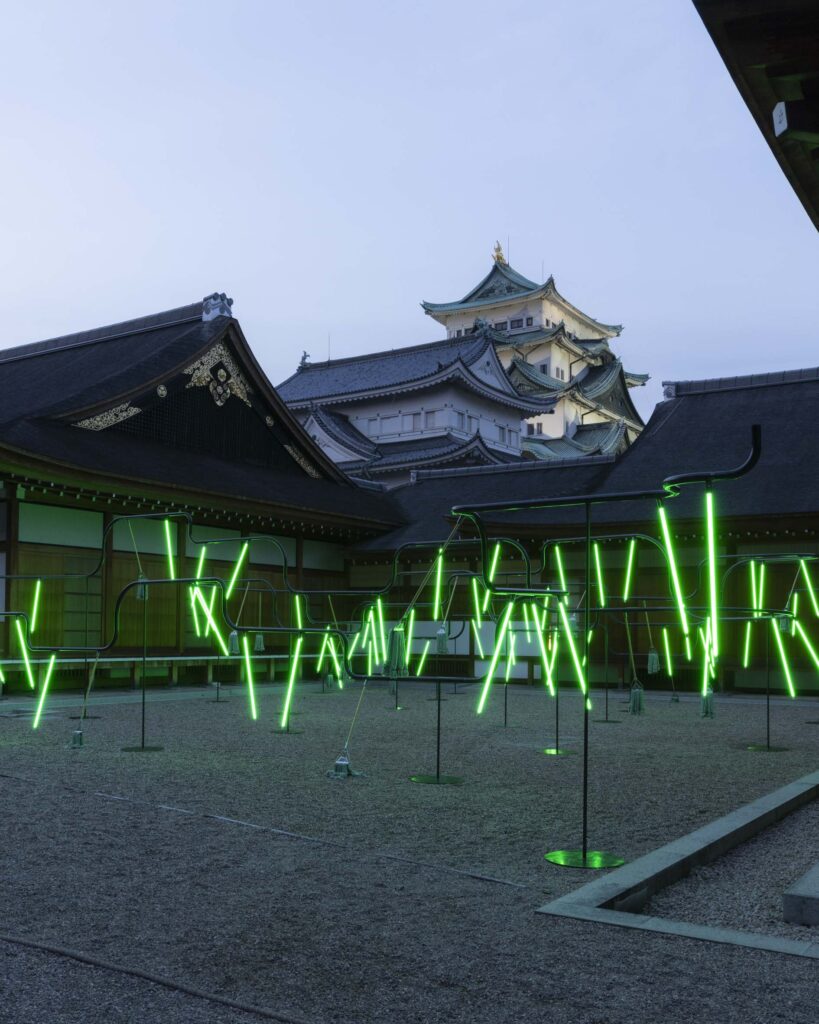

協働、経験、名古屋城

GROUP・井上岳(以下、GROUP):

玉山くんとは、名古屋城アートサイト2023と豊田市美術館での展示を協働したよね。それぞれのプロジェクトについて改めて振り返りたいと思っています。まず名古屋城のプロジェクトに関しては、会期の約半年前、2023年の6月ぐらいに主催者から話があがったんだよね。会期が始まるまでの時間が短いな、という印象があって。

玉山拓郎(以下、玉山):

敷地の名古屋城を見に行ったのが6月で、この時はどの場所で何を展示するのかも決まっていなくて、確かに急ぎのプロジェクトだった。

GROUP:

予算的にも時間的にもギリギリを狙った気がする。

玉山:

このスケールでもできると思っていて。経験上での感触でしかないのだけれど、これは複雑な感じで、関わっている人の人数や、それぞれの経験や関係性から考えて、もちろんあまりにもギリギリなことって、僕の中でもネガティブなことでもあるんだけど。「できそうなら実現したい」というところが先行するのかな。

GROUP:

最初の案からあまりスケールダウンせずに実現できたことが、僕にとってはとても驚きだった。普段の設計では、まず見積もりがあって、減額調整が入って、形や案が変わったりするので。かなりギリギリを狙えるんだなと。

玉山:

優先順位の設定なのかな。このアプローチは問題だなとも思っているけど、一番最初に立ち上がったイメージを忠実に生み出すことが前提になっていて。アイデアをダイエットすることは簡単だし、そこをうまくやって、予算を合わせていくことはできるけど、作品がスケールダウンするだけではない、もっと失われるものがある。意図しない方向に整えられてしまう。

GROUP:

なるほど。スケールダウンすると整えられて、多くの人にとっての想像の範囲内のものになってしまう。

玉山:

そういうふうになるのを避けたいというのがある。これは経験値でしかないのだけど、「これは実際に、現実に立ち上げられる」って思ったものは進める。そうじゃないものは出だしで変えていく。

GROUP:

そこの基準(クライテリア)の精度が高いんだろうね。このときは構造家の円酒さんも入ってくれていて、いつもより関係値が深かった気がする。関係値からクライテリアを最初に設定するのは面白いなと。ディレクターの方と玉山くんが以前プロジェクトをしたことがあるという前提が大事だったりする。

玉山:

関わってくれた方たちが僕の作家としての性質や人間としての性質を知っているから、あのスケールでつくれたのかもしれない。初めましてだった円酒さんの存在も大きかったと思っていて。例えば、「これは倒れないだろうな」とか「折れないだろうな」とか、今までは現場の勘みたいなものからでしか成立させてきてなくて、体感として分かっている素材の感触に、きちんと裏付けられた形態をつくれたことで、精神も形態も安定した。今後も協働したいと思えた。

形、ディテール、身体性

GROUP:

玉山くんは、形に関しても、全体のイメージを放り投げてくよね。それでいて細部の形はコントロールする。なにか理由があるのかな。

玉山:

絵画に例えると、自分で絵筆を持って線を引くことを避けているのは、造形的な個性を作家性として作品に取り入れたくないから。けれど素材や質感に関しては、フェティッシュの問題ではなく、良い悪いの基準が自分の中にある。これは社会一般の中でも存在している基準とそんなに乖離していないものだと思ってるんだけど、きちんと優劣がある。細部においては、作品にとって必要なクオリティーを設定しないといけないみたいな。それは逆に、僕としては無個性を目指してるのではなくて、細部のゆるささえもそこには、絵筆で線を引くのと似たような造形感覚が宿る気がしている。そうではなく、物質的な強度のクオリティーを高い水準に持っていくということでの匿名性みたいなものを目指そうとしている。

GROUP :

その細かいこと、一般的にディテールと言われることは、実はテクスチャーとして全体を覆っているから、実は「最大なこと」でもある気がする。そこへのコントロールというか、設計をしているんだなっていう発見があった。よーく見ないと分からないところが、物質的に全体を覆ってしまうっていうことは、物体に関する面白いところだと思う。その上で身体性を出さず、匿名性をつくっているのはなんでなの?

玉山:

匿名性をつくらずに粘土をこねるように魅力的な造形を生み出すことで豊かな世界をつくれるかもしれない。けれど、そこに自分の仕事はないかな。とてもつらいけど。

GROUP:

それってなんでなんだろう、例えば、生活していると、圧倒的に無個性の物質に囲まれている。今喫茶店で話しているけど、周りにはこのコップをはじめ身体性が出ているものなんて存在していない。そういうところへ、射程を広げるためのコンセプトなのかな。

玉山:

今言ったことも近いのかもしれない。工業的なもののあり方みたいな。芸術のためにやってて、生活や社会のためになにかやっているわけじゃないんだけど。やっぱり、前提として立場はモダニストで。 現代で作家をやっていく中で、モダニストであるには極端でないといけないと思っている。だから僕は造形を考えたくない。モダニズムの世界には造形の問題がずっとあったんだけど、そこに答えはない気がしていて。造形は一個人の人生を形づくるかもしれないけど、何も新しいものは生まれてこない。今そっちに未来がないと思ったときに、こういう質感を求めている。

GROUP:

モダニズムは、人が介在した経路を隠蔽することでもあって。このコップがどうつくられているのかは、もう分からないけど、これに価値があって使用されている。だれがつくっているのかは問題ではなくなっていることによる強みがモダニズムの特徴の一つだと思う。それによって、めちゃめちゃ取り引きされてネットワークが繋がっていく。世界中どこにでもこういうコップが存在できる。今話を聞いていると、そういうところにもしかしたら可能性というか、ある強度を見出しているのかなって。

でも実はそれを得るためには、身体的にも過酷な労働をしないといけないというのことを、名古屋城で知ることができた。たくさんパーツがあって、工場でつくられてきて、そこに職人さんたちの沢山の経路があって。そして、身体性をなるべく消す努力をしていくっていう作業によって、強度を獲得する。これは、確かにモダニズム的な立ちあらわれ方な気がするし、いつも見ている経路の隠蔽されたものたちがこんなふうになり得るんだと再発見できる可能性は確かにある。

さらにメディアの解像度が高くなっていることも大切な気がしていて。解像度が高いと、よりディテールが全体に影響を与えるようになってきているよね。どこまででも記録を拡大して見ることができちゃう。今そこを追求できる可能性がある気がする。

玉山:

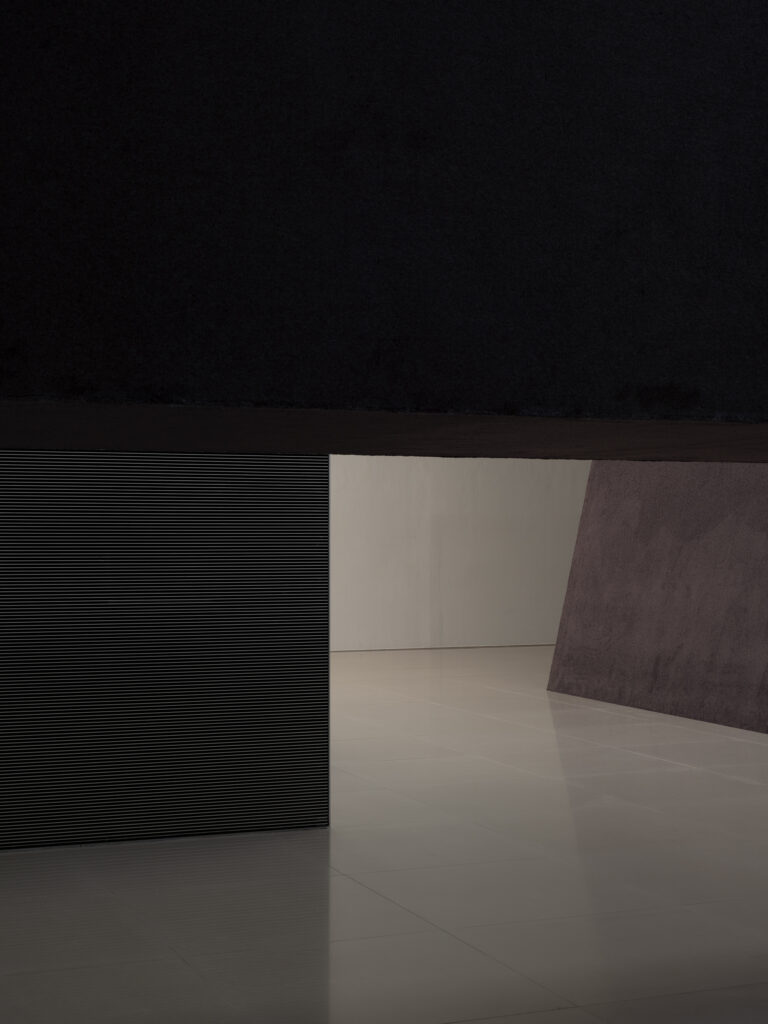

2025年の豊田市美術館での個展ではカーペットをつくったよね。あれはディテールの問題を宙吊りにしたと思っていて。ああいう均質な質感。しかもカーペットの密集している状態によって、空間の解像度をあいまいにしてる感じがする。

GROUP:

どこまで見てもカーペットだけという。ディテールは細かく存在しているけど、カーペットであるというのは面白いね、確かに。そういうのはほんとに可能性しかないと感じる。自分の身体性や経験を隠蔽をすることっていうのは、現代でも大事なことだと思う。例えば磯崎新さんがやっていた、身体性を消すこととはまた別の、今の隠蔽のあり方があるのかなと。僕たちの身の回りは、さっき話したように隠蔽されたものだらけなわけで。そういうことにもっと関わるための、それはもちろん政治的ではなく身体的ではない、実はもっと違うところに接続する可能性があると思う。

玉山:

現代の隠蔽に重ね合わさるのは面白いと思う。少し逸れるけど、70年代のもの派の人たちって、石とか木とかをただ置くようにものがあるだけで生まれる可能性を描こうとした。ある意味、作品って本来は匿名的なもので、そこに作家の身体は見えない。でも、もの派の方達の写真を見ると作家本人がけっこう写ってる。作品を持ってたり、いい顔して作品と並んでいたり。物だけで十分と言いつつ、それだと匿名性が強すぎて、作家の存在が消えてしまう。それこそ目指していることのようにも思えるけど、写真には自分を残してる。作品では自分の身体性を隠蔽しようとしているけれど、作家のプレゼンスを示すことも重要だなと。

豊田市美術館、自律性、都市開発

GROUP:

名古屋城のプロジェクトと比べて、豊田市美では長い設計期間があったよね。

玉山:

GROUPに相談した時点で、1年半以上前かな。僕に展示の話が来たのは2年前だった。

GROUP:

話をくれた時には、もう提案ができていたよね。豊田市美のプロジェクトは造形的にも最初からあった形が踏襲されている。実は、名古屋城とは、方向性が違うプロジェクトなのかなって思ったんだけど。

玉山:

予算の見通しがついてない状態で、あそこで実現しようとしていることに意味があると思ってたから。プランを守るための唯一の要素が、形を保持するっていうことだったんだと思う。形を途中で変えていっちゃってたら、プランというか、コンセプトごともしかしたら崩れている。いまだかつてない繊細な状況だったのかも。

GROUP:

形がほとんど全てである展示。内容も、さっきのディテールが全体になるというのと通じているところがあると思っていて。つまり名古屋城の時は、少しストーリーがあった。けど豊田市美は、そういうストーリー性みたいなものを意識的に消していると思うんだけど、それによってこう、違うネットワークに接続できる可能性を意識的につくろうとしてたのかなと思ったりしていて。

小さいストーリー、そういうキャプションに書かれるテキスト。これはこういう背景でこういうのでつくられていってというのではなく、ディテール、そして、もの自体によって、作品を自律させることにチャレンジしているのかなと思ったんだけど。

玉山:

それは確かにあって。もちろん、例えば、名古屋城のやつはそういう物語みたいなものだとしても、個人史的なものではなくて、場所に残っているような、記憶みたいなのを可視化した形だった。そもそも作家の持っている、プライベートでナラティブな要素は、暴力的だと思ってて。それをパブリックな場で予算をもってきて見せること自体が怖いことだと思ったりする。

どちらかというと、この作家や作品の持っている、ナラティブな要素に対する否定があったのかなと。そのことは自分の中で解消していかないといけないと思っていて。それが自分の一作家としての前提条件として考えている。そこへの意識は、単純に展覧会の規模だったり作品の規模と比例して、相対的に見えてくる気がして。だからこそ、豊田市美での展示ではその前提を強めに持っていた。

GROUP:

建築だと、自律性が再評価されだしたりしていて。幾何学があって、それで建築が自律しています、みたいな。とはいえ、みんなストーリーを持っている。そういった自律性を今後どのように乗り越えていけるのかが気になっていて。豊田市美の展示は、幾何学ではないよね。形態的にも構造的にも豊田市美を頼った形をある意味していて。けれど、目指しているものは独立して自律した作品であるというのが面白いと思っていて。そこに今後、幾何学だけではない自律性がまだ豊かに存在している可能性があると思えた。

玉山:

自分のインタビューを最近振り返ったときに、ちょっと、豊田市美術館や谷口吉生建築に対して言及しすぎてるかなと。本当はそこまで主題ではない。そこにある空間に対して、あの形が生まれているんだけど、谷口さんの手つきを理解した上で向き合っていると強く言えるほど、そこに集中して考えてたわけじゃない。こうしたものに頼らず自律しているけど、反発するように自律してるわけじゃない。

GROUP:

そうなんだよね。重ねていうと、歴史や谷口建築のコンテキストに合わせて作品や建築をつくることって一般的だと思うんだよね。むしろ建築をつくることで、全部のコンテキストをつくり直す、修正するというふうに考えることによる、設計のバリエーションの増え方に魅力があると思っていて。周りからいっぱい決められちゃって、予算もなくて、用途も決められちゃって、というだけではなくて、そもそも全体を実は決められる可能性みたいなものがあるのではと最近考え始めていて。豊田市美を通してそういうことを考え始めたのかも。もちろんあの作品は谷口建築の天井や窓にも操作しているけど、谷口建築と知った上であえて括弧に入れてみるということをしているのかなって思ったんだけど。そう考えてみると、この方法にはもっともっと可能性がある。

玉山:

やれることも、可能性もある。でも今の美術の現場で、現状においてはほとんど求められてない。世界の芸術祭を見ても、政治的、社会的な問題や、アクティビズム的なアプローチを前提としたテーマに偏っていて。そういう作品や作家じゃないと、プレゼンスを保てないし、期待もされない。そういう状態。

この間、似たような立場の作家と喋ってたんだけど、僕らは今潜伏期間に入る。迎合していくんじゃなくて、僕らは自分たちがやってきたことを守りながら、表現を維持するために意識的に潜らないといけない。表立ってると、どうしても関わる人も増えているし、商業的な依頼がきたりする。そうすると、否が応でも社会と接続していかないといけない。作品自体がその性質を持たなくても、イベントだったり、展覧会自体は社会的な性質を持ってしまう。そういうことって、意識的に避けないと言い訳ができなくなってくると思っている。

同時に豊田市美のような機会が、学芸員の鈴木俊晴さんみたいな人と、またこれから出会えるのかっていうのは分からない。それはもう10年、20年後の作品になっちゃうかもしれない。これは、一作家としては悩みどころではあるけど、悩んでもどうしようもないから。

スケール、意味性、ネットワーク

GROUP:

万博の木のリングや都市の開発を見て、どれも圧倒された。けれど一方で、たとえスケールは小さくても、世界を変えられるぞと思って活動をしている。赤瀬川原平さんの宇宙の缶詰しかり。けど、ああいう大きなものを見ると、小さいものをつくってもしょうがないみたいなことをどうしても感じてしまう。小さいものをいくら提案したとしても、届くところっていうのは、やっぱり小さい世界になっちゃうんじゃないか。

玉山:

ここから10年後にどうなるか分からないけど、現時点ではああいう宇宙の缶詰みたいなマスターピースを、今我々は生み出せないと思う。ポータブルなデバイスの中では、もう無限の空間性があって、そのスケールが生活になっちゃってるから、この思考を逸脱させる世界をつくることって難しいと思う。

GROUP:

確かにデバイスのネットワークは広すぎるよね。

玉山:

万博の木のリングを見に行かないといけないと思っているんだけど。韓国のアモーレパシフィック本社ビルはここ最近で一番興奮したかも。単純に大きい。

GROUP:

大きくてあれだけ、密度も高い。たしかに、軽い材料で最大の容積をとる方向とは違う方向で大きい。ここに可能性はあるのかも。そういう意味でもスケールっていうのは、もう一回、扱うべき課題だと思っているんだよね。というのも、これは都市開発みたいなものへも接続しうるテーマだと思っていて。今世の中を見渡してみると。そういう大きなスケールのことが沢山起こっている。そういうスケールというテーマをアートとして、それを単純にものとして扱っていることは、意外と少ないんじゃないかなと思っちゃう。

玉山:

あんまりそこを実践している人はいないかも、1つ浮かぶのは、エルムグリーン&ドラッグセットで、彼らはある意味では下品なんだけど、それを意識的にやってるという。透けて見えるお金のかかり方とか、それも彼らのアプローチの仕方かもだし。やりたくても、あんなことをやれる人もいない。ある意味で唯一無二かな。

GROUP:

豊田市美も名古屋城もスケールが大きいよね。そこに関してどのようなオブセッションがあるかを知りたい。例えば同じアートサイト名古屋城で展示されていたアーティストの寺内曜子さんの作品は、小さな手のひらサイズの作品に世界が収まっていた。けど、玉山くんの作品は純粋に大きい。

玉山:

寺内さんは思考に加えて、実際にも物理的に大きい作品を扱ってたから、その試行の中でスケールそのものを経験値としても強く理解している。その上で小さなものの中に思想的なスケールを孕んだアプローチをしていると思うのだけど、僕もそうなってしまったら、そこにはもう寺内さんという作家がいるし、自分がそうなってしまわなくていいと思っていて。スケールは、経験値の中で得られた勘でやっているところがある。一回会場を見に行けば、そのために必要なスケールや、そこで起こりうることが、簡単に想像ができる。ただ、名古屋城も豊田市美も、僕の中で良かったのは、思ってたより大きかったということ。他のプロジェクトではそれは起きなかった。それは、やっぱり協働があったからだと思う。それを求めてたんだなって自分は思った。事後的に冷静になって、気づいたことだけど、プロセスの中でもそう求めてたんだなって。

GROUP:

それは嬉しいね。僕はずっと大きいなと思いながらつくってたけど。協働することによって、スケールの所在みたいなものが曖昧になるのかな。どっちがスケールの責任あるんだろうみたいな。いろんな関係者との話し合いの中で、そこが宙吊りになる。大きさに関して、誰も触れないっていうか。

玉山:

そこは実は、打ち合わせしてる時に、少なくとも僕は言わないって決めてた。自分が言及すると、それを全体として自分が保持しないといけなくなる。それは他者に求めていた。みんなが宙吊りになる状態をつくろうとしていたのかな。

名古屋城と豊田市美術館という異なる条件下での制作を通じて見えたのは、協働が作品のスケールや匿名性のあり方を変化させ、新たな自律性を開く可能性である。形やスケールの判断はしばしば「宙吊り」になり、不確定さこそが新しい強度を生む——今回のインタビューは、その輪郭を描いた。

Group Form – Part 1: “Suspended Scale, Forms of Anonymity” Takuro Tamayama, Contemporary Artist

The word “collaboration” is more than just working together or dividing roles. It is the totality of countless decisions exchanged on site, the ambiguous negotiations over form and scale, and the criteria that emerge from relationships. In this series, Contours of Collaboration, we move between the fields of architecture and art to explore how collaboration shapes works and projects. For the first installment, we spoke with contemporary artist Takuro Tamayama, taking our collaborations on Nagoya Castle Art Site 2023 and at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art in 2025 as starting points for a discussion about anonymity, detail, autonomy, and scale.

Takuro Tamayama

Contemporary artist, born in Gifu Prefecture in 1990.

After studying at Aichi University of the Arts, completed a Master’s degree at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2015.

Drawing on familiar images, he creates objects reminiscent of furniture and everyday items, as well as interior spaces, combining them with vivid lighting and sound to produce installations.

Through minimal means, his works defamiliarize space or accentuate the laws of nature, stirring the viewer’s bodily senses and perception.

Collaboration, Experience, Nagoya Castle

Inoue Gaku (hereafter GROUP):

We worked together on both Nagoya Castle Art Site 2023 and the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art exhibitions, and I’d like to talk about each project.

First, with Nagoya Castle — we first spoke about it around June 2023, right? My impression at the time was that there wasn’t much time before the exhibition period started.

Tamayama:

I first visited the Nagoya Castle site in June, and at that point we hadn’t even decided on the exact location for the installation. It was definitely a rushed project.

GROUP:

With Nagoya Castle, it felt like we were aiming right for the edge in both budget and time.

Tamayama:

From experience, I felt we could pull it off at that scale — it’s just a gut feeling based on past work. Of course, something that’s too last-minute is a negative in my mind, especially considering the number of people involved and their respective experience and relationships. But if I think something is possible, the impulse to make it happen takes priority.

GROUP:

I was really surprised we could realize it without scaling down from the initial proposal. In architecture, there’s usually an estimate, then budget cuts, and the form changes or the proposal gets altered. It showed me you can actually aim right for the edge.

Tamayama:

It’s about setting priorities. This approach can be problematic, but my top priority is to fully realize the first image that emerged. Slimming something down is easy if you can do it well enough to meet the budget constraints. But what gets lost is not just scale — something more essential disappears. It becomes too “tidied up.”

GROUP:

I see. Scaling down tidies things up, but also makes them fall within the range of what most people can already imagine.

Tamayama:

Exactly — and I really want to avoid that. Again, it’s just a matter of experience, but if I believe something can actually be built, I push forward. If not, I change it from the start.

GROUP:

So your sense of criteria is very precise. This time we also had structural engineer Enshu-san involved, which meant more relationships than usual. Setting criteria based on relationships from the outset — that’s interesting. It also mattered that you’d worked with the director before.

Tamayama:

Yes, because they knew my temperament both as an artist and as a person, we could work at that scale. Having Enshu-san involved was huge — up to now, I’ve often relied on an on-site gut feeling: “this won’t fall over, this won’t break.” I know the tactile feel of materials, but this time we could back that up and create forms with structural assurance. That gave both the form and my mind stability. It made me want to collaborate again.

Form, Detail, Physicality

GROUP:

When it comes to form, you tend to let go of the overall shape but tightly control the details. Is there a reason for that?

Tamayama:

If I think in terms of painting, I avoid holding a brush and drawing lines myself. I don’t want to embed a sculptural personality as “artist’s style” into the work. But when it comes to materials and textures, I do have strong ideas of good and bad — not in a fetishistic sense, but in a way that aligns with certain general social standards. I think there’s a hierarchy, and in the details, I need to set the quality level the work requires. That’s not about aiming for impersonality; even looseness in details can carry a sculptural sensibility like drawing a line with a brush. Instead, I aim for a kind of anonymity that comes from bringing the physical quality of materials up to a high standard.

GROUP:

Those small things — what we usually call “details” — actually cover the whole as texture, so they’re a huge factor. I realized you’re designing, or controlling, at that level. The fact that something barely noticeable can still envelop the whole physically is fascinating. Why aim for anonymity instead of letting physicality show?

Tamayama:

Maybe I could create a rich world by shaping clay into attractive forms and showing my hand, but I don’t think that’s where my work lies — even if it’s difficult.

GROUP:

Why is that? In daily life we’re surrounded by overwhelmingly impersonal objects — like here in this café, starting with this cup, there’s almost nothing with visible physicality. Is your approach a way to extend your range into that territory?

Tamayama:

That’s part of it. It’s about the way industrial objects exist. I make art, not things for everyday life or society, but my basic stance is modernist. In working as a contemporary artist, I think modernism now has to be extreme. So I don’t want to think about form. Modernism has always had a “form problem,” but I don’t think there’s an answer there. Form might shape an individual life, but it doesn’t generate anything new. If I feel there’s no future in that direction, I look for this kind of material quality.

GROUP:

Modernism hides the paths of human involvement. You don’t know how this cup was made, but it has value and is used. Who made it isn’t the point — that’s one of modernism’s strengths. That anonymity allows it to circulate globally. Listening to you, I feel you’re finding potential or strength there. But achieving that requires physically demanding work, as I saw at Nagoya Castle — many parts, made in factories, each with craftsmen’s hands in the process, and then an effort to erase physicality to gain strength. It’s a very modernist way of making things, and it lets you rediscover how the hidden processes behind familiar objects could manifest.

Also, high-resolution media matters — as resolution increases, details affect the whole more. You can zoom endlessly now. That might be an opportunity to pursue.

Tamayama:

The Toyota Museum piece was carpet, right? That suspended the question of detail — such a homogeneous texture. The dense pile blurred resolution.

GROUP:

Yes, no matter how closely you look, it’s carpet. The detail exists, but it’s “carpet” — that’s interesting. It feels like pure potential.

GROUP:

Concealing one’s own physicality and experience is still important today. I wonder if there’s a contemporary way of concealment, different from how Isozaki did it. As we said earlier, the things around us are already full of concealment. Engaging with that might connect to something beyond politics or physicality.

Tamayama:

Overlaying it with contemporary concealment is interesting. In Japan’s art world, the Mono-ha artists of the ’70s showed the possibilities that emerge just from the mere presence of things. Their works had great anonymity — just placing a natural stone. But those artists often appear in photos with their works, showing themselves. Maybe they needed that because pure material presence erases the artist’s presence entirely. I find that interesting: hiding physicality in the work but still signaling the artist’s presence.

Toyota Municipal Museum, Autonomy, Urban Development

GROUP:

Compared to Nagoya Castle, we had a long design period for Toyota.

Tamayama:

Yes — when we discussed it, it was a year and a half before the show. I’d gotten the exhibition offer two years earlier.

GROUP:

By the time we spoke, you already had a proposal. The form from the start was carried through. In a way, it was a different kind of project from Nagoya Castle.

Tamayama:

Yes — even without a clear budget outlook, I felt there was great meaning in what we were trying to realize there. The one thing I could absolutely preserve was the form. If we’d changed that midway, the plan — even the concept — might have collapsed. It was an unusually delicate situation.

GROUP:

It was an exhibition where form was almost everything. In Nagoya Castle, there was a bit of a story; at Toyota, you deliberately erased narrative. Was that to consciously create the possibility of connecting to a different network? To let detail and the thing itself make the work autonomous?

Tamayama:

Very much so. Even if Nagoya Castle’s narrative was site-based rather than personal history, I see private narrative elements as potentially violent. Showing them in a public, budgeted context is frightening. So I had a kind of negation toward narrative. It’s not a big “concept” but a precondition I hold as an artist — and I think that awareness emerges proportionally to the scale of the exhibition or work. So at Toyota, I held to it strongly.

GROUP:

In architecture, autonomy is often discussed now — geometry that supposedly makes a building autonomous, but in reality, everyone still has a story. The Toyota work wasn’t geometric; in some ways it relied on the museum’s form. Yet it aimed to be autonomous. That suggests there’s a richer kind of autonomy beyond geometry.

Tamayama:

I think I was trying to do that. Looking back at interviews, I might have talked too much about Toyota Museum and Taniguchi Yoshio — it wasn’t the main subject. The form came from the space, but it wasn’t about depending on or rebelling against Taniguchi’s hand.

GROUP:

Right — usually people design to fit a building’s history or context. But I’m interested in the idea that making a work or building can actually remake or rewrite the whole context. Through Toyota, I started thinking more about that — and that there’s more potential in bracketing the architecture, even while altering ceilings and windows.

Tamayama:

There’s huge potential, but also big problems. In the art world now, biennales and festivals mostly demand narrative and political themes. Those are the only works/artists that maintain presence. A peer recently said: we’re going into a dormant phase. Not to conform, but to protect what we’ve been doing, we have to submerge ourselves. If you’re visible, you inevitably get more commercial offers, more social connections. Even if the work itself isn’t social, the event or exhibition will be. That’s something we have to consciously avoid.

At the same time, I don’t know if I’ll ever get another opportunity like Toyota with someone like curator Suzuki-san. Maybe it’ll be 10 or 20 years before another such work — but there’s no point worrying.

Scale, Meaning, Network

GROUP:

Lately I’ve been thinking about scale — from the wooden ring at Expo to urban developments. They’re all impressive, but when you’re doing small-scale activities, even if you believe they can change the world, big things can make you feel like the small works can’t reach very far.

Tamayama:

Maybe in ten years this will change, but right now I don’t think we can make a “masterpiece” like Akasegawa’s Canned Universe. Portable devices already hold infinite space; that’s the scale of life now. It’s hard to create a world that pulls thinking out of that.

GROUP:

The network of devices is huge.

Tamayama:

The Amorepacific HQ in Korea excited me more than anything recently — simply for its sheer size.

GROUP:

Yes — and density. Not “light materials for max volume” big, but big in a different way. That’s why I think scale is a theme worth handling again — it can connect to urban development. Surprisingly few artists treat large scale purely as a thing.

Tamayama:

Almost no one. Maybe Elmgreen & Dragset — deliberately vulgar, visibly expensive, consciously doing it. Few can pull that off.

GROUP:

Both Toyota and Nagoya were large-scale. I’m curious what kind of obsession you have with scale. For example, Terauchi Yoko’s small hand-sized works contained worlds, but your works are simply big.

Tamayama:

Terauchi’s scale is backed by her experience working with physically large works — for me, scale comes from instinct built through experience. Once I see a venue, I can easily imagine the necessary scale and what could happen there. What was great about Nagoya and Toyota is they turned out bigger than I expected. That didn’t happen in other projects — and I think that was because of collaboration. In hindsight, I see I was seeking that.

GROUP:

That’s nice to hear. I always thought they were big, but maybe collaboration makes authorship over scale ambiguous — whose responsibility is it? Conversations with all the stakeholders suspend that question.

Tamayama:

I actually decided not to mention scale in meetings. If I did, I’d have to take sole responsibility for holding it. I wanted to ask that of others — maybe I was trying to create a suspended state where everyone was in between.

Through making under the very different conditions of Nagoya Castle and the Toyota Municipal Museum, we saw how collaboration can change the scale and anonymity of a work, opening possibilities for new forms of autonomy. Decisions about form and scale often became “suspended” — and it was in that uncertainty that a new kind of strength emerged. This conversation traced those contours.

_1-1.jpg)